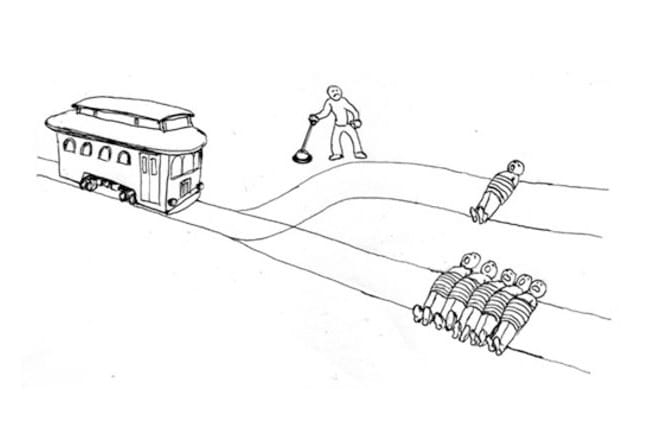

I sometimes get the sense that utilitarianism has become the dominant view in pop philosophy, with deontology seen as a close -- or perhaps the only -- alternative. The most famous thought experiment in philosophy, the trolley problem, distinguishes between the two views. Five people are tied to a trolley track. A trolley barrels down the track and approaches a junction with another track. There is one person tied to the second track. You can pull a lever and switch the trolley from the five-person track to the one-person track. Utilitarians (typified by John Stuart Mill) pull the lever so that only one person dies instead of five. Deontologists (typified by Immanuel Kant) wouldn't pull the lever because by pulling the lever you are actively committing murder and murder is bad.

The 'in' thing these days seems to be that utilitarianism is correct and deonotology is dumb. At least that's what you see in the comments of the Trolley Problem Memes Facebook page.

And to be fair, utilitarianism is a pretty good ethical system. With a few basic assumptions (e.g. we care about human happiness) and infinite computing power, you can get a sensible answer to pretty much any ethical quandary by tallying up the utils (happiness points) for any given action. There are paradoxes that emerge from this approach, but overall it's basically sensible. Deontology has its merits too though, perhaps the chief among which is that it relies on simple-to-follow rules instead of intractable calculations of future outcomes.

What's missing from this debate is any mention of virtue ethics. Virtue ethics, instead of focusing on outcomes or actions, is primarily interested in virtues, or positive moral qualities of the individual. Virtue ethics is ambivalent about the trolley problem - on the one hand, actively killing someone by pulling the lever can have dramatic negatives consequences on the psyche a la Crime and Punishment, but choosing not to save to the five people on the first track when you know that you could have if you so choose can be equally character-demolishing.

One trolley problem-esque thought experiment for virtue ethics is the corruption problem. You are in a position where you could run for political office. You know that power corrupts, and according to virtue ethics being corrupted is bad. However, there is another candidate running for office, and you know that the power of political office will corrupt the other candidate more than it will corrupt you. The utilitarian would say "it's better than you run for office, because if the other guy wins then he'll do worse things because he will become more corrupt." A virtue ethics purist, however, might say that your responsibility is to focus on your own virtues, and thus you should avoid the corrupting occupation even if this choice results in net negative consequences for society. (Thought experiment proposed by R. Aryeh Klapper.)

In any event, virtue ethics has been subject to criticism in the rationalist community. Scott Alexander the Great in particular wrote a series of posts in 2013 arguing against virtue ethics in favor of utilitarianism (link, link, link).

...we can debate important moral questions – like abortion, or redistributive taxation – until the cows come home, but this is in fact only the appearance of debate since we have no agreed-upon standards against which to judge these things...

The interesting thing about virtue ethics is that it is uniquely bad at this problem... For example, in Kant’s famous “an axe murderer asks you where his intended victim is” case, the virtue of truthfulness conflicts with the virtue of of compassion (note, by the way, that no one has an authoritative list of the virtues and they cannot be derived from first principles, so anyone is welcome to call anything a virtue and most people do).This is a valid critique of virtue ethics, but I think it misses the point of what virtue ethics is about. In real life, most people are not confronted by runaway trolleys or inquisitive ax murderers very often. I personally find myself in morally ambiguous situations maybe once a year on average. Consequentialism and deontology, while useful for resolving the hard problems when they do come up, simply don't play much of a role in my day-to-day life.

When a person wakes up in the morning, he faces a litany of seemingly trivial choices about what to eat, how should he behave at work, how he should interact with his family, how to apportion his time, etc. Utilitarianism has little to say in these choices, other than things like "if you exercise you'll live longer, but then again if you live longer you might be unhappy during those extra years and watching Netflix will make you happy now..." and deontology can say "The categorical imperative says you must exercise 30 minutes a day." But neither of these seem like the correct approach to even framing the issue of whether and why you should exercise.

Enter virtue ethics. Virtue ethics answers the question "what is the proper path that a man should take for himself in life?" Virtue ethics promotes the concept of Eudamonia, or human flourishing. Virtue ethics differs from utilitarianism and deontology because it views the flourishing of the individual -- that is to say you personally -- as an important teleological end into itself. While utilitarianism cares about universal happiness and suffering and deontology cares about universal moral rules, virtue ethics cares about you. Virtue ethics is a project to build humans into the best possible versions of themselves. Of course, within virtue ethics there is some debate as to what the best possible version of a person looks like, just like there is debate within any other ethical framework. But the questions of "should I exercise now" or "how should I spend my time this evening" are questions that begin to make a lot of sense in a virtue ethics framework.

For the most part, virtue ethics isn't interested in the big once-a-year moral dilemmas, and it would be happy to hand off that job to utilitarianism. But by the same token, utilitarianism isn't particularly interested in the role that virtue ethics plays either. If you're a billionaire with a million dollars to burn and need to decide which charity to give that money to, on a utilitarian frame the answer to that question is astronomically more important than your decision of whether or not to exercise, to the point where the exercise question doesn't even register as a worthwhile ethical problem. Virtue ethics, on the other hand, will say "hey buddy, it's great that you gave a million dollars to charity, but first of all it's a tiny portion of your wealth so you're not really that much better than anyone else and also you still need to exercise because being physically active is a virtue just like generosity is."

II.

Perhaps one of the great losses to the world when religion lost its philosophical standing is that questions of individual virtue took second stage to political questions which - by dint of affecting large numbers of people - obfuscated the need of every person to independently build their own personal character. This sentiment is typified in the second-wave feminism mantra "the personal is political." From a utilitarian perspective, of course, there is a great deal of truth to this. The overall physical well-being of people, especially people who are members of vulnerable groups, depends largely on policy.

But there is a sense in which relegating all individual well-being to the political sphere is profoundly dangerous. Practically speaking, if political change is untenable, the vulnerable individual is done for. If the individual has to wait for society to remove barriers to his success before moving forward in life, he has no recourse but to either passively wait or attempt to effect societal transformation. The latter, being the more active approach, tends to feel like the more noble choice, so political activism becomes the moral activity.

Political activism, when done correctly, does have utilitarian moral value assuming that one candidate dominates the other one in total utility and that you made the right choice. The website 80,000 hours estimates that a vote in a US election is worth somewhere on the order of 100,000 to a million dollars in terms of the expected impact on the economy (which is a weak metric for well-being, but it's what we have). It also cites a Brookings Institute study that door to door electioneering can get one vote for every 14 contacts and phone banking gets one vote for every 38 contacts. On the other hand, leaflet and email campaigns had little to no statistically significant effect. Interestingly, there is a surprisingly large incidence - on the order of 20% - of people who change their minds on a political issue due to social media according to this Pew study.

So from a utilitarian standpoint, social media activism might actually be one of the most impactful and important ways you can affect people's lives in a positive way. Swinging one Facebook friend to vote for the better candidate is worth more than most people's annual salaries.

But think about how dystopian this becomes, even for a person such as myself who spends, er, a very utility-maximizing amount of time arguing with people on the internet. All of a sudden "being ethical" turns into "spending every waking hour in flame wars on Twitter." What you eat doesn't matter. Whether you exercise doesn't matter, except in that it takes time away from social media. How you treat your friends, family, colleagues, barely matters. All that matters is that sweet, sweet, utility maximization by convincing people on the internet to vote for the right person. And under utilitarianism, that is an ethical imperative.

Maybe this example is silly, because I'm overestimating the impact that social media has on policy outcomes and human well-being. But there are examples that hit a lot harder. There was a Japanese official, Chiune Sugihara who was a vice consul during World War II. Sugihara took it upon himself to hand-write thousands of visas, for up to 20 hours a day, for Jews so that they could escape the Holocaust and come to Japan. He produced as many visas in a day as would normally be produced in month. He slept little and wrote until he could literally write no more, knowing that every hour that he slept would mean the deaths of at least dozens of people. He saved 5,558 Jews from their deaths by the hands of the Germans and is undoubtedly one of the great heroes of the Second World War.

But somehow it seems unreasonable to make this kind of heroism ethically normative for everyone. Realistically we can expect heroic individuals who completely disregard their own needs in order to help others to occur every once in a blue moon. And most people don't find themselves in positions where they have an opportunity to accomplish such gargantuan feats of utility maximization.

Ethics needs to have a normative default for normal people living boring, non-heroic lives. And people need to have a sense of what it means to live a good life -- that is a happy, healthy, meaningful, and psychologically rewarding life. And it turns out that a big part of living a good life is being selfless and generous, but that's not the entirety of it.

Utilitarianism believes in the maximization of well-being, but has no clear definition of what well-being looks like. It uses things like standards of living, wealth and "happiness" as proxies, but it turns out that A) wealth is not necessarily a great indicator of happiness, especially between countries (link) and B) "happiness" is ill-defined and notoriously difficult to achieve. And politics, at the end of the day, is mostly concerned with questions of wealth. And that's why, though politics is certainly necessary for achieving well-being, it is far from sufficient. For people to actual be better off, they have to understand what "better off" means.

Virtue ethics defines well-being, and importantly, states that even under the best of circumstances, well-being requires effort on the part of the individual, and that's a feature, not a bug. Well-being means investing time in your family. It means eating healthy food. It means being nice to people. It means taking your work seriously. But above all, it means that psychology - in terms of your personality and character traits -- is really, really, important.

III.

A lot of religions and ancient traditions of ethical thought are essentially virtue ethics systems. Confucianism, for example, emphasized virtues like benevolence, justice, filial piety, honesty, and loyalty. Rabbinic Judaism, with its myriad rules and commandments, is also essentially a virtue ethics system in many interpretations. Though some laws in Judaism have a strong deontological vibe ("don't murder" probably just means "don't murder") many of the rituals have ethical symbolism, meant to inculcate virtues in its practitioners. The obvious example here is "don't cook a kid goat in its mother's milk," which is meant to teach the virtue of compassion. The Bible and Talmud are also replete with stories and lessons about virtuous behavior.

The import of virtue ethics fully crystallized in the Judaism with the advent of the mussar (ethics) movement in the 18th century. In the mussar framework, ethical behavior was seen as Judaism's paramount value, in some sense superseding the ritual aspects of the religion. That being said, the mussar movement was fully Orthodox in terms of practice, but it shifted the emphasis towards ethics. One of the major insights of the mussar movement was that not only is personal character important, it is possible to improve your personal character with constant, vigilant attention and, critically, personal character improvement is man's chief responsibility in life.

Adherents of the mussar movement had a number of methods to achieve personal character goals. One prominent mussarist, Eliyahu Dessler, incorporated Freudian psychology into his teachings. Other schools of thought were even more unorthodox. Yisrael Salanter, the founder of the movement, recommended that people chant mantras to instill in themselves personal virtues. An old joke goes that in one mussar school, a student sat swaying back and forth and repeating the mantra ich bin a gornisht - I am nothing (meant to invoke humility) - vociferously and emphatically, over and over again. Another student, seeing this display, starts chanting the same matra even more loudly than the first student. The first student picks up his head and angrily yells "I can't believe this guy thinks he's a bigger gornisht than I am! One yeshiva (religious academy) in Nevarodok, Russia had a practice of sending its students out to bakeries and request to purchase hardware appliances so that the students would build personal resilience and humility in the face of mockery.

The mussar movement was essentially wiped out in the Holocaust. Its only real remnants are books written by its adherents and 15 minute seder (study period) or shmuess (sermon) devoted to mussar in some yeshivot. And this begs the question: why wasn't there a serious mussar revival movement in Orthodox Judaism? The Lithuanian tradition of Talmud study refounded itself after the Holocaust, as did many streams of Hassidic Judaism. Why not mussar?

I think the answer here is that, in some sense, people knew that the mussar movement was a failure. As a teacher of mine once remarked, "if you do everything the mussar books tell you to do, you turn into the kind of person no one really wants to be around." Some historical accounts seem to support this take; Chaim Grade's book The Yeshiva is an excellent historical novel portraying the darker side of the Nevarodok mussar tradition. While mussar was perhaps noble in its conception, its methods and overall obsessiveness left much to be desired.

The word mussar (מוסר )is mostly famously related to the biblical verse (Proverbs 1:8) "שְׁמַע בְּנִי מוּסַר אָבִיךָ וְאַל תִּטֹּשׁ תּוֹרַת אִמֶּךָ" - listen, my son, to the instruction (mussar) of your father, and do not forget the teaching (Torah) of your mother. There is a bit of an oddity in this verse, which is that the teaching of the law (Torah) was historically considered the province of males in the patriarchal society of the Bible. In this verse the gender roles are reversed - the mother is teacher of the law and the father is giving ethical instruction. I claim that the gendered coding here is no accident. The verse here in Proverbs is describing an ancient practice of fathers teaching their sons "how to become men" which is distinct from the teaching of the law. Virtue ethics, at its root, are values that parents instill in their children, and in particular values that fathers teach their sons.

For whatever reason, males seem to have a particular need for this sort of instruction, perhaps due to greater levels of testosterone-fueled aggression relative to women. Men are in particular need of having their basest instincts reeled in, and it's often only a father figure who can play that crucial instructive role. Fatherlessness is one of the most important predictors of male incarceration (source) as well as a number of other outcomes like school performance and behavioral issues that are more pronounced in boys than in girls (source).

It is perhaps for this reason that personal improvement preachers like Jordan Peterson have become so popular among males. Peterson is notorious (among other reasons) for his exhortation that people clean their room (literally and metaphorically) as a critical aspect of their character development. Many find this lesson comical, but it makes perfect sense in terms of virtue ethics. In virtue ethics, the little details of our lives - like the cleanliness of our living space - reflect and affect how we see ourselves. And unsurprisingly, "clean your room" is also exactly the kind of instruction that fathers have been telling their sons around the world, from time immemorial.

Speaking of time immemorial, I came across this cuneiform tablet at the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

There's a certain irony to the fact that #MeToo movement in 2018 in America has an ally in a 4400 year old message that a father tells his son how to behave around women. This text is part of a genre known as "wisdom literature" -- of which the book of Proverbs is also a part -- which is in many ways synonomous with virtue ethics. A tablet like this doesn't give us a utility maximizing function (though, incidentally, there were some cuneiform texts with algebra problems in the same display case) nor does it really establish a deontological system of rules that everyone is obliged to obey. Rather, this is advice -- wisdom -- from a father to his son about how to live a good, ethical life.

I think there may be a lesson here, about what we need to effect societal change in areas like, say, the prevalence of sexual assault. The political and criminal justice systems might be able to make a dent in predatory male behavior via the standard deterrents. But the first line of defense against bad behavior shouldn't be politics or the justice system, it should be individual ethics. And most of the time individual ethics isn't about utilitarianism or deontology -- most people don't even know what those words mean. In the real world, for most people, ethics is simply the values that good parents teach their children.

Otherwise known as virtue ethics.