I.

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, by Jonathan Haidt (2012), rose to fame largely because of its explanation of the political differences between conservatives and liberals in the United States. The topic has become ever more relevant, as the 2016 election has shown just how far American politics has been polarized. So though this review may come relatively late -- as book reviews go -- there is ample reason to revisit Haidt’s work on this topic six years later.

The Righteous Mind belongs to a category of literature I would put in the broad category of “human evolutionary behaviorism”. Though the topic has antecedents in Darwin, the serious scientific study of human behavior on a wide scale through the lens of experimental psychology as such is relatively young. I would personally point to the behavioral economics studies of Kahneman and Tversky in Thinking Fast and Slow as the origin of the discipline. That may be an arbitrary line, however, because people have been seriously thinking about the motivations for human behavior for a very long time, and anthropologists and psychologists have contributed value insights since the births of their respective fields. The reason why I emphasize the recentness of the field is that...as far as I can tell, our scientific knowledge of the principles governing human behavior largely depends on a few decades of studies. This also tends to mean that if you’ve read one popular book on the subject, there are pretty significant diminishing returns for each subsequent book that you read.

My personal introduction to human evolutionary behaviorism was The Moral Animal, by Robert Wright (1994). The Moral Animal focused on an evolutionary psychology explanation of human behavior, particularly behavior such as altruism. From my recollection - it’s been a while since I’ve read the book - The Moral Animal essentially makes the claim that altruistic behavior can be selected for via evolution due to A) personal interest, in the sense that reciprocal altruism can benefit everyone in the long term and B) the “selfish gene” which “cares” about spreading itself (i.e. the gene), not about the individual person, so people with similar genes (especially families, but in theory can extend to everyone in a species) behave altruistically because it’s generally good for the spread of closely-related genes. The Righteous Mind considers these two possibilities but also emphasizes a third possibility: group selection, which is the idea that groups which behave altruistically within themselves tend to outlast groups that don’t. I’ll say a bit more about this later, but I just want to put the book in the context of some of the other ideas that are out there.

Anyway, The Righteous Mind is divided into three sections, each of which has a central claim. Haidt puts a lot of emphasis (maybe even too much emphasis) on the main takeaways of each section and chapter, so I’m not doing much editorializing here when I describe what they are.

Claim 1: Human moral thinking is primarily driven by intuition/emotion/sentiment, not reason. Haidt here contrasts the view of Plato, who believed that emotions ought to follow the intellect, with David Hume, who stated that “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” Haidt is firmly on the side of Hume, using a metaphor of “the elephant and the rider.” The elephant is emotion and intuition, the rider is the intellect. According to Haidt, the elephant does most of the work, the rider is just along for the journey. More precisely, when it comes to morality, the intellect is used to defend the conclusions that intuition has already decided, not the other way around. The way Haidt proves this claim is via a battery of experiments wherein he asks participants how they would judge a variety of scenarios which intuitively feel very wrong but wherein it is difficult to see any utilitarian downside (e.g. one-time consensual secret incest between a brother and sister with birth control). Participants will often struggle for a while to come up with an argument for why something they intuitively believe to be wrong is actually bad, and then when they fail to come up with an argument they don’t necessarily change their view.

Claim 2: Morality is about more than harm. Here, Haidt discusses his “Moral foundations theory” which posits that instead of just being about suffering and happiness, intuitive morality comes in six different “flavors”, which he calls moral foundations. The flavors are Care/Harm, Liberty/Oppression, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, And Sanctity/Degradation. Care/Harm is the easy one, it’s about empathizing with other people (and cute animals) and caring that they are happy and don’t get hurt. Liberty/Oppression is about freedom from tyrannical people who abuse their power. Fairness/Cheating has to do with making sure that people are rewarded for good behavior, punished for bad behavior, and don’t get more than their fair share (liberals) or than they deserve (conservatives). Loyalty/Betrayal focuses on being loyal to your group and involves things like treating your country’s flag with dignity or not speaking ill of your country on a foreign radio station. Authority/Subversion relates to respecting social hierarchies, like children honoring their parents or students listening to their teachers. It is also the basis of religious morality and submission to the authority of God. Finally, Sanctity/Degradation is the foundation that includes sensibilities about cleanliness, sanctioned and illicit sexual behavior (e.g. incest), and foods that one may eat (kosher for Jews, halal for Muslims, and not eating insects for secular Westerners).

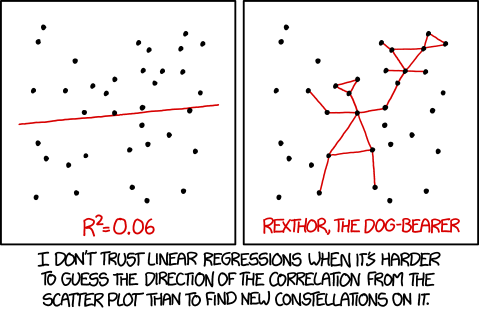

Haidt argues that although people have some sort of innate proclivity towards all of these moral foundations, some people place the emphasis in different places. In particular, liberals (in the American sense, i.e. progressives) tend to emphasize care/harm and liberty/oppression (in the sense of certain kinds of oppression, like that of minorities and marginalized groups) over the other moral foundations, having little respect for authority hierarchies, loyalty, or most forms of sanctity. In contrast, conservatives tend to have a more balanced palate, appreciating all six moral foundations pretty much equally. Haidt also demonstrates these proclivities via questionnaires about moral intuitions among people across the political spectrum and obtaining graphs that look like this:

Haidt says that part of the reason why liberals have such difficulty swaying conservatives is that liberals don’t how to engage the “taste buds” of loyalty, authority, and sanctity, which are core conservative values.

Claim 3: Humans are naturally groupish and hive-minded, and this explains a lot of our values, especially the ones that conservatives tend to value more. Haidt’s metaphor for this section is “We Are 90 Percent Chimp and 10 Percent Bee.” There are a lot of obvious examples of this phenomenon, like religions, sports fans, political tribes, and so on. Haidt argues that this is not just an emergent aspect of collective human behavior; rather he thinks - drawing on the work of Emil Durkheim - that we have a sort of psychological “switch” that turns individual sense of self into an expanded, collective self. In particular, synchronized physical movement, such as marching in the army or the ecstatic dancing of Aztec tribes, can expand the mind from the individualistic “chimp” state to the collectivist “bee” state.

Collectivist mentality can entail a reification of “society” as an entity that can be harmed. If you burn a flag in private, even if no one is being visibly harmed, there is a non-quantifiable sense in which you are harming your country’s social fabric (no pun intended) by removing yourself from the collective and damaging one of its sacred symbols. Loyalty, authority, and purity all start to make sense when seen in this light. Conservatives tend to be strong believers in the “sacred platoons” of Edmund Burke; the religions, clubs, and teams that bind people together. These platoons usually involve sacred symbols, hierarchies, strict demarcation of ingroup and outgroup, etc. They will also sometimes involve costly signaling rituals (like fasting on Ramadan) which demonstrate a commitment to the collective. In return, the collective provides increased “social capital” in the sense of trust and altruism between members of the group. Diminished social capital within societies means less trust and higher transaction costs. (For example, Orthodox Jewish diamond dealers in New York are able to outperform their competition because of their internal high-trust social network.) Being part of a collective also has psychological benefits, and Haidt here notes a positive correlation between individualistic societies and suicide prevalence.

This is where group selection comes in. Unlike the outspokenly atheist proponents of evolutionary psychology such as Richard Dawkins, Haidt believes that religious tendencies are a feature which emerges natural selection, not a “bug” that arose as a byproduct of otherwise beneficial cognitive tendencies (such as seeking out conscious intent in nature, which is a beneficial skill in social contexts). According to Haidt, because religious societies tend to be high in social capital, groups with religious beliefs and practices tended to be more prone to survival than non-religious groups. As such, proclivities towards religious beliefs may have actually been selected for via natural selection.

Overall, Haidt says that conservatives (including people from many traditional and religious societies) understand the value of social capital and the invisible fabric of society in a way that liberals (and libertarians) don’t. Liberals would thus be well-advised to heed the moral flavors that they tend to neglect, as they ignore the greater part of the moral palate at their own peril.

II.

One point that Haidt mentions briefly, although not nearly as strongly as he should, is that the book is about descriptive morality, not prescriptive morality. In other words, Haidt's work - particularly regarding moral foundations - is designed to describe how people in the real world behave, not how they should behave. There’s one line in the book where he says that his preferred moral theory is utilitarianism, but he doesn’t dwell much on this point. Instead, the thrust of the book tends to be toward convincing liberals that the intuitions about morality held by conservatives are worthwhile paying attention to. Haidt himself seems to have started out as a liberal who grew to appreciate certain aspects of conservatism and traditional societies, and he thus finds himself in a position of urging his (presumably liberal, but also open-minded) readership to follow suit.

Sarah Constantine has a great post where she groups together Haidt, Jordan Peterson, and Geoffrey Miller (whose work I am not familiar with) as “psycho-conservatives”. In short, psycho-conservatives are people who believe that some form of conservatism/traditionalism is optimally suited to human psychology, and this entails a broad swath of implications for things like gender roles, criminal justice policy, race relations, and so on. And there does seem to be some sort of merit to this argument. But Sarah makes the following point:

“If you used evolved tacit knowledge, the verdict of history, and only the strongest empirical evidence, and were skeptical of everything else, you’d correctly conclude that in general, things shaped like airplanes don’t fly. The reason airplanes do fly is that if you shape their wings just right, you hit a tiny part of the parameter space where lift can outbalance the force of gravity. “Things roughly like airplanes” don’t fly, as a rule; it’s airplanes in particular that fly.”

In other words, while it seems like most ancient, traditional and conservative civilizations had to hit all of the taste buds on the moral palate to construct a society optimally in tune with human psychological needs, that might only be because we haven’t yet figured out the precise mix of ingredients necessary to create an optimal society without the deleterious effects of traditional values (diminished status of women, inter-group fighting, false beliefs, excessive obsession with symbolism, etc.)

Psycho-conservatives thus tend to run afoul of the naturalistic fallacy -- that evolutionary “is” entails moral “ought”. Robert Wright in The Moral Animal was better about this and was very careful to state that though evolutionary psychology can inform the project of morality to some degree, the moral thing to do is often the opposite of what our evolution-based intuitions would suggest. For example, people often have an intuitive preference for harsh punishment, but from a utilitarian standpoint, it would seem that cutting off the hands of thieves and stoning adulterers is not a good way to run a society.

And this, I think, is where Haidt needs to be taken with a grain of salt - to continue the taste bud metaphor. We might all have some level of predilections toward all of the six moral foundations, but the devil is in the details - and more specifically, the mixing quantities. The tongue’s taste buds have very different sensitivities to different flavors. For example, the taste threshold for strychnine, a bitter toxin, is 0.0001 millimolar, while the threshold for sucrose is 20 millimolar, a difference of over five orders of magnitude (source). The same might be true for the best mix of the moral foundations. There’s no compelling a priori reason to believe that liberal emphasis of care/harm and dismissal of most aspects loyalty and hierarchy is the wrong way to do things from a prescriptive standpoint. In the simplified world where the six moral foundations are the only axes along which moral systems vary, the utilitarian problem reduces to finding the correct set of weights along each of those axes which maximizes human flourishing...and we don’t know what those weights are. And beyond that, they may vary from person to person, society to society, and environment to environment. That’s why politics (in the sense of creating good policy) is hard.

At the same time, though, politics is still worth doing. Why? Because “multiple optimal solutions for different individuals, societies, and environments” is not the same as “all solutions are optimal.” Acknowledging that diversity may exist in the way to construct a healthy society does not mean that moral relativism is the answer. (In his conclusion, Haidt also rejected relativism, but again didn’t really expand on how to go from his moral foundations theory to a non-relativistic moral system.)

I have the benefit/misfortune of a journey in the opposite directions as Haidt’s, going from a very traditional/conservative society (Orthodox Judaism) to a very liberal one (secular academia in Israel.) And while Haidt is enamored with the benefits of traditional society, I have close acquaintance with the dark underbelly...and it’s not pretty. Many forms of Judaism, including the more liberal forms of Orthodox Judaism (like Modern Orthodoxy, my background) do a reasonable job of promoting human happiness and flourishing despite their very different weighting of the moral taste buds than secular society. And like Haidt said, the strict rules do go a long way in promoting a strong sense of community and social trust. I still maintain strong social ties to the Orthodox Jewish world, largely because the community there is stronger and more fulfilling than anything I’ve managed to find outside of it thus far. That being said, there is a point at which religious communities go too far, and I’ve seen it. The obvious examples are the extremely insular Hassidic communities in the US and the Haredi (Ultra-Orthodox) communities in Israel that prevent their adherents from studying secular subjects, including basic science, math, and English. I am sure that the sense of community is stronger among those groups than among the Modern Orthodox; insularity results in that almost by definition. At a certain point, we have to put our foot down and say...no. That is not an optimal solution. You can’t trade “strong sense of community” for literally everything else involved in the human experience, like having some basic knowledge about the world around you. The harrowing accounts of people who have left that world, like Shulem Deen’s All Who Go do Not Return, leave you with a sense that while these communities have some positive aspects, they are dystopias, pure and simple.

So where do I draw the line between acceptable diversity and unacceptable relativism? That’s also a hard question. I suppose I’m not really interested in lines, so much as proximity to optimal solutions. And I think that this is something that people within a society intuitively feel, and it’s something that’s quantifiable. I know that for me, living as a secular person is better than an Orthodox person. Yes, I miss lots of things about Orthodoxy, and I often dip back into that social world when I feel the need. But I feel more comfortable with myself living outside of the Orthodox bubble than inside it. Most importantly, as a secular person, I have true intellectual freedom; I can think what I want without it being judged according to the tenets of Orthodox theology. Of course, this is all still my personal experience. I feel like my personal experience should be generalizable, but interindividual variability is a very real thing.

Really what we need is a reasonably good battery of questions which captures human flourishing on a variety of axes (maybe coupled with some neurological measures, though that may end up in Goodhart territory) see how different societies measure up on average. This is, of course, the great utilitarian project, and at the moment it seems like it is being won the Scandinavian countries, which are very heavily atheist but also keep many of the cultural trappings of religion (link). This might be a good direction to go in. On the other hand, Scandinavian countries also have a lot of other things going for them in the political and economic realm, so it’s a bit hard to disentangle their politics from their religious predilections (and the two might be causally related anyway).

In sum...maybe all six moral foundations are kind of important, and we should think about psychology when designing policy. But as long as we have reasonably acceptable metrics for how happy people tend to be in different kinds of societies, we don’t need to resort to a priori reasoning from psychological first principles. Instead, we can directly measure what kinds of solutions work and what don’t, and then do more of the stuff that works and less of the stuff that doesn’t work. And sure, we’re talking about things that can be tough to quantify and prone to various sorts of measurement error, but that’s life. Reasoning based on evidence about the target that you’re actually interested in will always be better than armchair philosophizing about how people are wired. People are wired in complicated and diverse ways, but some moral systems seem to produce strictly better outcomes than others, and that’s what we should be looking at when it comes to prescriptive morality.